Aga Khan Award for Architecture 2019: Shortlisted Projects from the Middle East

Out of more than 400 globally nominated, 20 projects have been selected for the 2019 Aga Khan Award for Architecture. Three of them from the United Arab Emirates only.

The 20 shortlisted projects for the 2019 Aga Khan Award for Architecture were announced today. The projects will compete for US$ 1 million in prize money.

In January, an independent Master Jury reviewed hundreds of nominations. The 20 shortlisted projects are now undergoing rigorous investigations by a team of experts who visit and evaluate each project on-site. Their reports are the basis for the Master Jury’s selection of the eventual laureates. It should be noted that projects commissioned by the Aga Khan or any of the institutions of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) are ineligible for the Award. To be eligible for consideration in the 2019 Award cycle, projects had to be completed between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2017, and should have been in use for at least one year.

The winner will be announced later this year in Kazan, Russia.

Congratulations to the United Arab Emirates as three projects have been shortlisted.

I picked up the shortlisted from the Middle East:

Bahrain

Revitalisation of Muharraq: This site, inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, is an exceptional testimony to the pearl trade in the Arabian Peninsula, on which Bahrain thrived during the 19th century. In a visionary effort to maintain the spirit of this historic city a number of conservation projects as well as some new buildings and schemes for the public spaces have been implemented by an NGO and the government. A part of the project, titled “Pearl Route” and consisting of architectural properties, oyster beds and parts of the seashore, encapsulates every aspect of the pearling economy. A pathway allows visitors to discover the historical area, along with a newly built visitor centre and two public squares. It is an ongoing project on a great scale, which aims to conserve and adapt ancient structures, as well as create new ones and make them coexist harmoniously. This broad project demonstrates a sensitive approach to heritage conservation and contemporary public space planning.

Client: Sheikha Mai Al-Khalifa, Authority for Culture & Antiquities Conservation Department, Manama, Bahrain

Architect: Authority for Culture & Antiquities Conservation Department, Manama, Bahrain. Design: 2010-2013 (330,000 m²). Completed: 2013-ongoing.

Lebanon

Jarahieh School, in Al-Mari: The school provides not only educational facilities for children from 300 Syrian refugee families, but is also a hub for community activities and the settlement’s only secure shelter in the event of snowstorm or earthquake. An adaptation of the Expo 2015 Save the Children Italy Pavilion in Milan, it is a source of pride for the community who helped redesign and build it. The open-sided pavilion was transformed into a series of enclosed spaces around a courtyard through a participative process that used envisioning exercises, focus groups and interviews to engage with children, NGOs, municipality members, teachers and parents. All transformation materials were locally sourced, including sheep’s wool to insulate against cold and heat, regulate humidity, resist fire and provide sound insulation.

Client: Save the Children Italy, Jusoor NGO, Sawa for Development and Aid NGO, Beirut, Lebanon

Architect: CatalyticAction (London, UK). Design: 2016 (422 m²). Completed: 2016

Oman

Muttrah Fish Market, in Muscat: The new market celebrates the continuity of the region’s trade and fishing traditions, while also catering to Oman’s growing tourism industry. Situated at Muttrah’s harbour, a top tourist attraction, it houses a rooftop restaurant in addition to the market itself. The design exemplifies contextual regionalism, respecting the scale and integrity of the traditional context whilst adding new and dynamic elements. The curved wall that defines its spine reflects the radial shape of the corniche and bay area, and has light-filtering pierced decoration. The canopy’s form was inspired by the sinuous flow of Arabic calligraphy, exploiting the play of light and shadow. Its aluminium fins provide shade, natural ventilation and an ephemeral appearance that contrasts with the simple solidity of the concrete structure below.

Client: Municipality of Muscat, Oman

Architect: Snøhetta, Oslo, Norway. Design: 2009-2012 (5,769m²). Completed: 2017

Palestine

Palestinian Museum, in Birzeit: The Museum, clad in local limestone, crowns a terraced hill overlooking the Mediterranean. Its design was directly inspired by the surrounding rural landscape with which it blends seamlessly. Not only does the building interact aesthetically with its environment but it also is the recipient of the LEED Gold certification as a result of its sustainable construction techniques. The gardens cascading down the edifice tell the history of Palestine’s vegetation and agriculture, whilst the interior highlights Palestinian culture in its galleries, educational and research facilities, and administrative offices. The Museum aims to promote Palestinian culture in the Arab world and internationally – not only as a memorial to its past but also as an incubator for creative projects and programmes in the present and the future.

Client: Taawon-Welfare Association / Palestinian Museum, Ramallah, Palestine

Architect: Heneganh Peng Architects, Dublin, Ireland. Design: 2012-2013 (40,000 m²). Completed: 2016

Qatar

Msheireb Museums, in Doha:

Four historic courtyard houses dating from the early 20th century have been remodelled and extended to accommodate unified, state-of-the-art museums that together comprise a central element of the development of downtown Doha. The subject of each museum relates directly to the occupations or visions of those who originally lived in them, making them authentic mouthpieces for Qatari history and culture. The domestic architecture was reinstated using traditional construction techniques and materials; new services and technologies were integrated into floor areas and hidden recesses. Skylights were introduced for interior lighting. Careful attention was given to the arrangement, paving, water elements, and landscaping of the open courtyards. The most significant new architectural intervention was the creation of a new subterranean gallery below one of the houses.

Client: Msheireb Properties, Doha, Qatar

Architect: John McAslan + Partners, London, UK. Design: 2012 (10,350 m²). Completed: 2016

United Arab Emirates

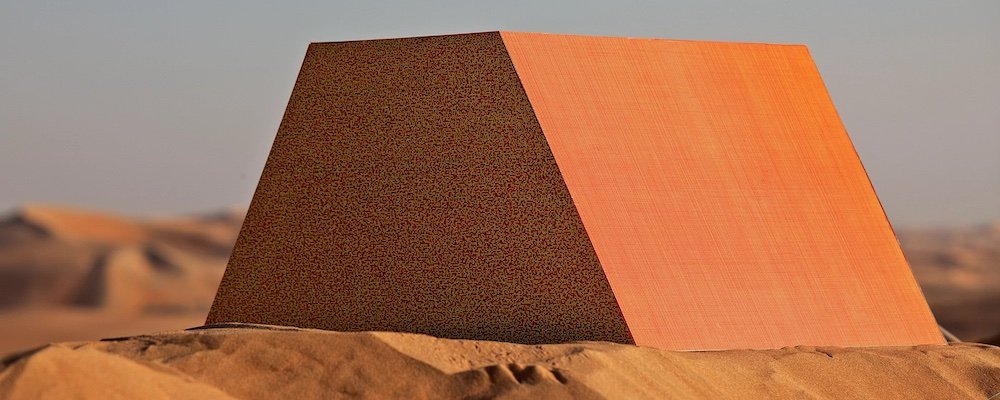

1) Concrete at Alserkal Avenue in Dubai

Alserkal Avenue, a former industrial complex in Dubai has been transformed into a cultural hub. This project took four existing warehouses and reimagined them to create Concrete, a flexible, multipurpose space for artists and cultural events in the centre of the complex. In order to maximise the area for events, the services were consolidated at one end of the building. The entrance and events space, with a flexible floorplan containing four 8-metre high pivoting and sliding walls, are situated close to The Yard, the district’s main outdoor public space. The front façade has large-scale, translucent doors that open onto The Yard, forming a symbiotic relationship between indoors and outdoors and allowing activities to flow between both spaces.

Client: Alserkal Avenue LLC, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Architect: OMA: Office for Metropolitan Architecture, Rotterdam, Netherlands. Design: 2015-2016 (1,250 m²). Completed: 2017

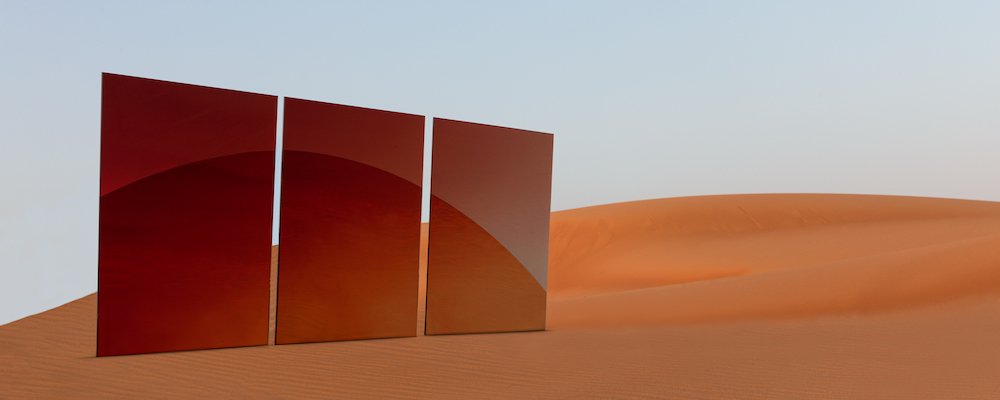

2) Al Mureijah Art Spaces, in Sharjah:

The Sharjah Art Foundation, a cultural institution that emerged from the Sharjah Biennial, wanted to invest in non-museum spaces and simultaneously reclaim historic links to the city centre. Five dilapidated buildings in the Al Mureijah neighbourhood offered the perfect urban and architectural setting for a contemporary art venue. Now renovated and combined with additional outdoor exhibition areas, the five buildings provide a range of interior and exterior spaces to experience art in a variety of ambiences. Rooftops were cleared and interconnected to serve as extra open-air galleries and particular attention was given to natural lighting. The Sharjah Art Spaces were designed so as to allow the continued preservation of almost 40% of the urban fabric whilst creating a new gathering place for local and international art enthusiasts.

Client: Sharjah Art Foundation, United Arab Emirates

Architect: Mona El Mousfy, Sharmeen Azam Inayat, Sharjah, UAE. Design: 2010 (9,289 m²). Completed: 2013

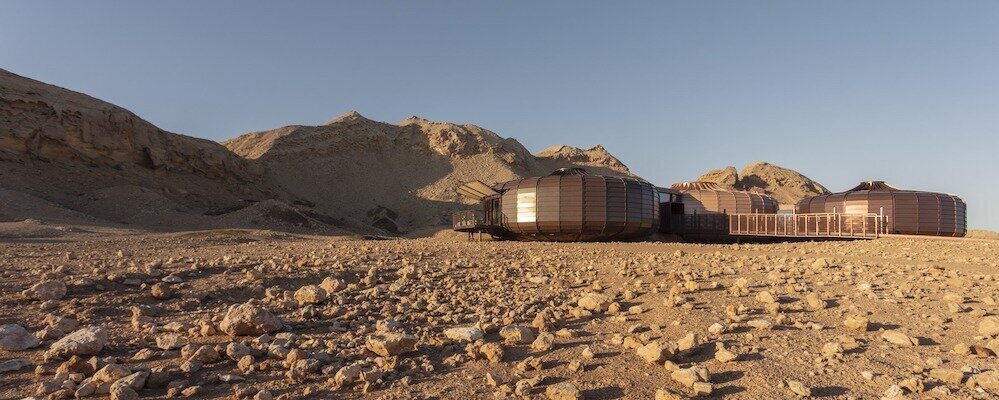

3) Wasit Wetland Centre, in Sharjah:

Part of a much larger project to clean up and rehabilitate this ancient chain of wetlands along the coast, the Wetland Centre aims to provide information and education about this unique environment – and to encourage its preservation. The architecture of the centre uses the existing topography of the site to minimise the structure’s visual impact. Upon arrival, visitors are led underground along a pathway into a linear gallery with a transparent wall that allows them to observe birds in their natural habitat. The centre also has shops, restaurants, lecture halls and offices. Eight bird observation structures are built around the wetland route. The site offers a safe place for reproduction for local fauna and migrant birds, and a unique opportunity to learn about and connect to nature – while serving as a green lung for the inhabitants of Sharjah.

Client: Environment and Protected Areas Authority, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

Architect: X-Architects, Dubai, UAE. Design: 2012 (200,000 m²). Completed: 2015

The 2019 Award Master Jury

The nine members of the 2019 Master Jury are: Anthony Kwamé Appiah, an Anglo-Ghanaian American philosopher; Meisa Batayneh, founder and principal architect of maisam architects & engineers; Sir David Chipperfield, whose practice has built over 100 projects for both the private and public sectors; Elizabeth Diller, a founding partner of a design studio whose practice spans the fields of architecture multi-media performance and digital media; Edhem Eldem, a Professor of History at Boğaziçi University (Istanbul) and the Collège de France; Mona Fawaz, a Professor in Urban Studies and Planning at the Issam Fares Institute of Public Policy at the American University of Beirut; Kareem Ibrahim, an Egyptian architect and urban researcher who has worked extensively in Historic Cairo; Ali M. Malkawi, a professor at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design and a founding director of the Harvard Center for Green Buildings and Cities; and Nondita Correa Mehrotra, an architect working in India and the United States and Director of the Charles Correa Foundation. For more information, please see the biographies of Master Jury members.