In a Park: How a Forgotten Brick Reframes Domestic Life

In Singapore, a modest apartment renovation by L Architects reimagines domestic life through red brick, greenery and the spatial logic of a park. In a Park shows how a forgotten material can bring warmth, intimacy and a quietly generous way of living back into the home.

There are cities you visit and cities you come to know. Singapore is, for me, the latter: precise but generous, quietly modern yet stubbornly tied to memory. Its parks and neighbourhoods have a reassuring cadence — a particular red of brick here, a low bench there — that feels both domestic and civic. It is this colour and the sensibility behind it that L Architects have captured so deftly in In a Park, a renovation that speaks as much about material affection as it does about horticulture.

I have always been drawn to buildings that know how to be humble. In a Park is a renovation of a compact three-bedroom apartment in the north-east of the island, commissioned by a horticulturist. The brief was simple and honest: the household had outgrown its original layout and needed a home that could better accommodate an expanding plant collection. What struck me in early conversations about the project — and what stayed with me after seeing the finished space — was a small phrase from the client: he loved plants, but he did not “wake up to them”. That gentle observation became the project’s hinge.

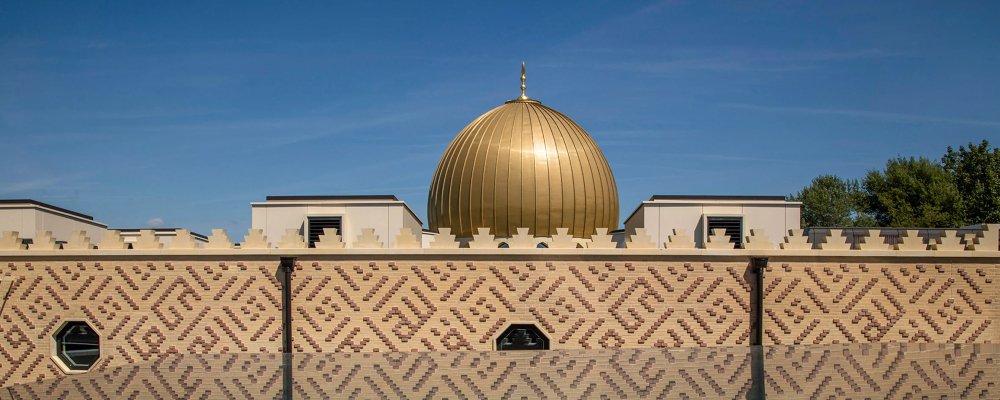

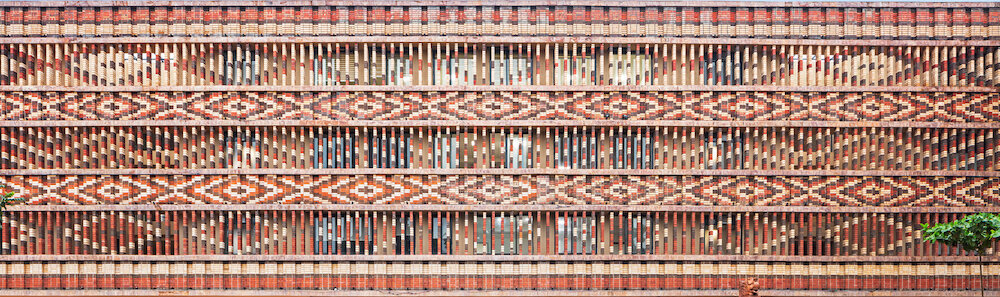

Rather than treating plants as ornaments, L Architects set out to make greenery part of everyday movement and routine. They distilled the idea into something I find profoundly Singaporean: an interior that borrows the spatial logic of a park. In public parks across the city, there is a memorable detail that often goes unnoticed — the double-bullnose brick. Once ubiquitous around benches, planter edges and walkways, these rounded bricks carry a softness and a history that modern materials tend to erase. Reintroducing that brick within a domestic interior feels like an act of cultural archaeology.

The double-bullnose bricks themselves came with a story. The local factory had stopped making them; only 571 pieces remained in a last inventory. That scarcity could have been a problem. Instead, it became a narrative device: the remaining bricks were treated with reverence, used sparingly and intentionally. The bricks’ rounded edges allowed the architects to model gentle curves — a tessellated freestanding wall that breathes between study and living area, and a curved bench between study and dining that functions as a shared threshold. These are subtle interventions, but they change how the apartment is inhabited. You sit, you pass, you pause — and the brick holds those small moments with an almost intimate warmth.

Red brick, in this setting, does more than provide texture. It establishes a tone. There is a warmth in that colour that cosmetics like paint cannot mimic. It softens natural light, it frames a plant without competing with it, and it invites touch. When I visited, I found myself lingering on the bench, feeling the coolness of the rounded edge and appreciating how the material somehow makes the apartment feel less like a private cell and more like a shared room in a neighbourhood house. In that sense, the bricks do what good architecture does best: they translate the public memory of a city into private comfort.

The project does not rely on theatrics. There is no high-tech wizardry, no overblown gesture. Instead, In a Park celebrates restraint, craftsmanship and the rediscovery of value in the ordinary. It is a reminder that innovation can be quiet: in how a common brick is shaped and placed, in how a plant is allowed to follow the path of morning light, in how a bench becomes a place for conversation. For a place like Singapore, where the new constantly rubs against the old, such gestures feel vital.

L Architects, founded in 2016 by Lim Shing Hui, have built a practice around precisely this sensitivity — the human scale of design, the tactility of materials and the stories embedded in everyday objects. Their work spans residential, interior and experimental projects, and it is easy to see here how a focus on ordinary elements can yield extraordinary atmospheres. In a Park is not simply a renovation; it is a small manifesto about care and continuity.

If there is a lesson in this apartment it is this: the value of a material is not only in its novelty but in how it shapes inhabitation. The double-bullnose brick, long absent from modern production lines, becomes a vessel for memory and for new rituals. It reconnects the domestic to the civic, and in doing so, makes both richer. In a city I love for its clarity and warmth, this project feels like a quiet, necessary second act — one that asks us to look at the things we take for granted and to imagine how they might live better with us.

In the end, In a Park is a small love letter — to plants, to red brick, and to Singapore itself. It proves that the most persuasive architecture is often the least boastful: an interior that welcomes the day, invites people to linger, and turns an ordinary material into something almost intimate. I left the apartment thinking about benches in the rain, the rounded edge of a brick under my palm, and how a modest architectural gesture can recalibrate the way a home is loved.

Pictures by Jovian Lim