Transform! Designing the Future of Energy

The exhibition at Vitra Design Museum focuses on the transformation of the energy sector from the perspective of design.

Energy is the main driving force of our society; energy is political, energy is invisible, energy is omnipresent. All of the buildings, infrastructure and products related to the generation, distribution and utilisation of energy are created by human beings. Consequently, design plays a key role in the current transition to renewable energy.

What are the criteria for designing an energy-efficient product? How can design contribute to an increase in the use of renewable energy? How can industries, government policies and every one of us help to achieve the transition to a sustainable future?

The elimination of fossil fuels must be pursued with urgency in order to reduce global carbon emissions and stop climate change. Just as the dependency on fossil fuels has influenced even the smallest details of our daily lives, the progressive shift to renewable energy sources will have a corresponding effect on our future. This is where design comes into play, as it is necessary to give form and shape to the new age of sustainable energy.

Therefore Design needs to mediate between scientific research and end users. It identifies how innovative technologies can be utilised and it is often the decisive factor in whether new solutions are ultimately accepted or rejected by consumers.

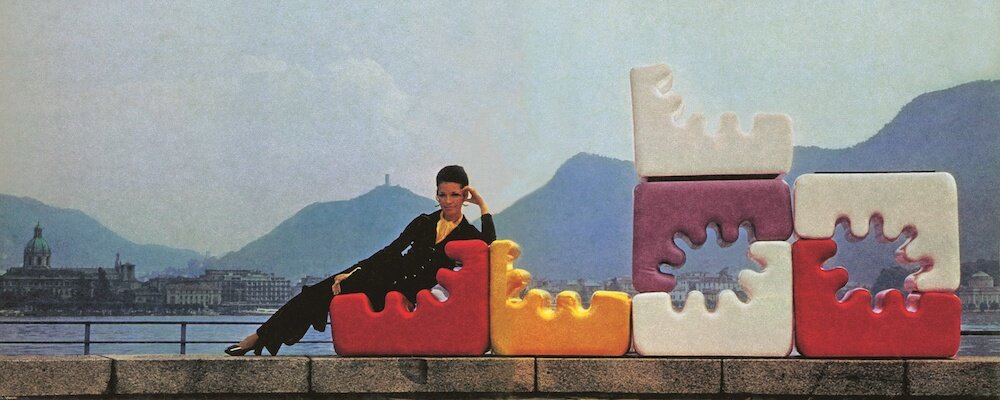

The exhibition ‘Transform! Designing the Future of Energy’ starts with a focus on human beings and our bodies, and then widens the view to examine our everyday objects, our cities and the entire energy landscape. The displays will include examples of innovative and experimental product design, speculative design projects, films, architectural archetypes and visionary future concepts.

Human Power

At the start of the exhibition, visitors are invited to discover their own potential for generating energy. By pedalling on stationary exercise bikes, they can see how long it takes to produce enough electricity for common activities such as brewing coffee, browsing the web or taking a hot shower.

The word ‘power’ has both physical and political meanings. A selection of international posters and protest signs, handbills and leaflets reflects the evolution of energy policies and the ability of every individual to influence them: from the US government programme ‘Atoms for Peace’ to the anti-nuclear movement, from the promotion of renewable energy sources to civil resistance against solar power plants and wind farms installed by global corporations.

A slide show on the ‘petroleumscape’ illustrates how crude oil has shaped our landscapes and lifestyles as a source of energy – and how challenging it will be to liberate ourselves from the dependence on fossil fuels.

Energy Tools

The second section of the exhibition features products, prototypes and experiments for living ‘off-grid’ – without a connection to the conventional energy infrastructure. Pauline van Dongen integrates photovoltaic cells into apparel designs, such as her Solar Shirt (2015), or into fabric panels like Suntex (2022). Stefan Troendle developed his Hydrogen Cooker as a prototype for a green hydrogen-powered stove. The Papilio street lamp by Tobias Trübenbacher meets its own energy needs with a built-in wind rotor. Marjan van Aubel’s solar-powered pendulum lamp Sunne (above) imitates the atmospheric quality of natural sunlight, from sunrise to sunset.

With this speculative project ‘Available Networks’, Pablo Bras explores the potential of capturing incidental flows of energy in and around the home – from the wind blowing across the roof to rainwater running down the gutter pipe to produce small amounts of power. An assortment of historical projects was also chosen for this section to show that the idea of energy self-sufficiency inspired designers from early on. The so-called Solar Do-Nothing Machine, created by Charles and Ray Eames in the 1950s, already used photovoltaic technology to set a kinetic sculpture in motion.

Transformers

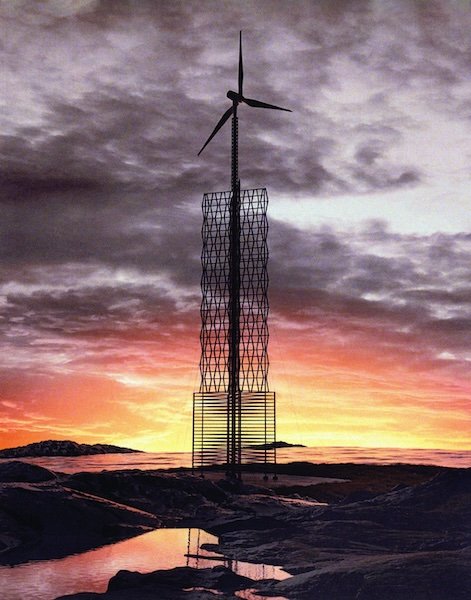

In the third part of the exhibition, innovative approaches in the areas of architecture and mobility. The building sector alone is responsible for roughly a third of global energy consumption and the percentage attributed to the transportation sector is almost as high. The Powerhouse Brattørkaia (hero picture) in Trondheim, design by Snøhetta, is recognised as the world’s northernmost energy-positive building – it produces more than twice as much energy as it consumes, feeding the surplus back into a local microgrid.

The Plus Energy Quarter P18 in Bad Cannstatt, developed by Werner Sobek in collaboration with AktivHaus, features a self-sufficient heating system, thanks to a combination of heat pumps, photovoltaic thermal collectors and the controlled ventilation of interior living spaces. The Day After House by TAKK architecture, in turn, demonstrates that high-tech solutions are not mandatory for improving the energy efficiency of existing buildings: due to a clever spatial configuration with various climatic zones and the use of natural insulation materials, this apartment requires almost no supplemental heating.

The paradigm shift from the combustion engine to the electric motor is also increasing the importance of solar energy within the realm of transportation. At the vanguard of this transition are experimental solar-powered automobiles like the Covestro Sonnenwagen, which can cover a distance of up to 500 km with a solar array measuring roughly 2.5 sqm. However, companies like the German startup Sono Motors are now integrating photovoltaic technology into production vehicles as well. To achieve greater sustainability in courier and parcel services, the company ONOMOTION has invested in e-cargo bikes and a combination of electric motor and muscle power.

All forms of energy production, distribution and storage have a spatial footprint, whether through the extraction of the required raw materials, for the construction and operation of buildings for generating or transforming power, or for the infrastructure needed to store and distribute energy.

Future Energyscapes

The final section of the exhibition is devoted to the field of research including new typologies for energy storage, such as the Energiebunker in Hamburg or Hot Heart, Carlo Ratti’s pioneering proposal for the intermediate storage of thermal energy in the city of Helsinki. Other visionary ideas for the future production of energy are also presented, from the wind turbine models designed by students from ECAL/Lausanne for the Canadian island of Fogo, to the hypothetical ‘Eneropa’ conceived by Rem Koolhaas’ Netherlands-based think tank AMO. Examples of historic predecessors include Herman Sörgel’s idea for a huge land mass supplied with hydroelectric power, introduced in the 1930s as the ‘Atlantropa’ project, or Buckminster Fuller’s ‘World Game’ and the notion of managing the world’s entire energy reserves and resources with a global computer network.

‘Transform! Designing the Future of Energy’: 23 March – 1 September 2024, Vitra Design Museum

Hero image: C.F. Møller Architects, Copenhagen International School Nordhavn, 2017 © Adam Mørk / Architect: C.F. Møller Architects