Advent 2025: St Peter Church by Le Corbusier

To close this little Advent pilgrimage I wanted a Le Corbusier landmark— but not the familiar hilltop chapel at Ronchamp. Instead one in a former mining town whose industrial grit somehow suits his concrete poetry.

Stop Four: Firminy, France.

Le Corbusier began the project in 1961, and it carries the melancholy of unfinished intentions: he died in 1965 and the work stalled and resumed in fits and starts. Construction began in 1973, halted in 1978, and only picked up again in 2004. The church was finally inaugurated on 29 November 2006, forty-one years after the architect’s death — which gives the place a curious, almost posthumous patience. José Oubrerie, who had worked with Le Corbusier, took care to keep the spirit of the design alive; the result feels like a completed thought rather than a museum piece.

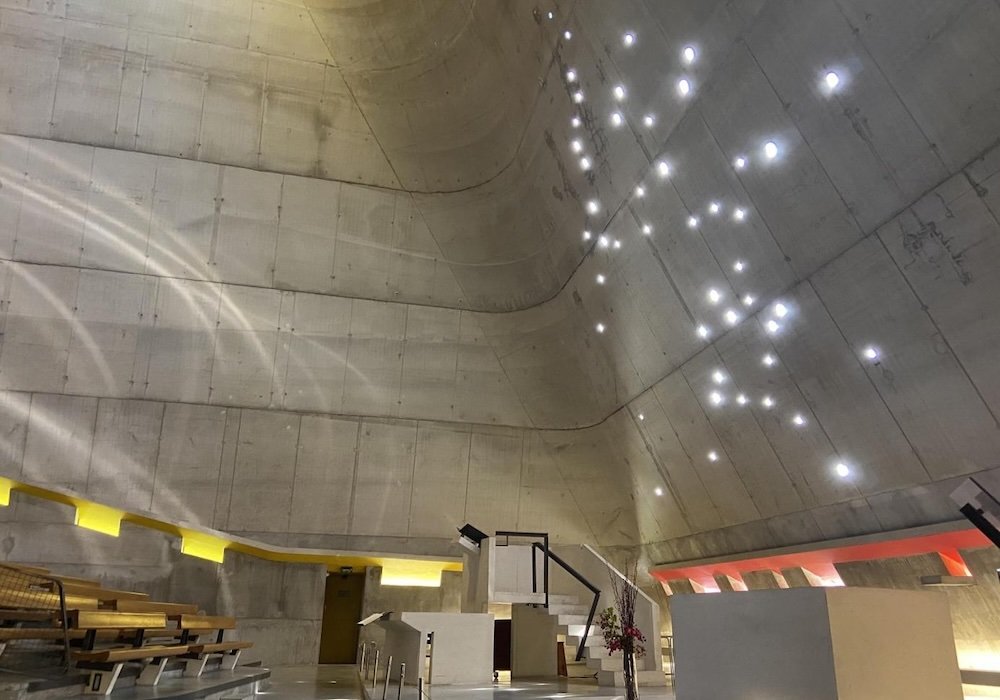

What greets you is a bold, geometric silhouette: a square base that projects upwards and becomes a truncated cone, a pyramid that softens into a circle — a tidy metaphor for the earthly moving towards the sublime. The vault peaks at about 33 metres, and the whole concrete shell shelters a nave and a weekday chapel, while the lower glazed facades open onto an exhibition space. It is monumental without being theatrical; the mass is honest, almost companionable.

The church is both austere and strangely intimate, an exercise in light and mass that still manages to hold a human heartbeat.

Light is where Firminy sings. Le Corbusier treated illumination as an instrument, arranging openings and light-boxes like notes on a score. Some are set to catch important days — Good Friday and Easter — while others trace a subtler choreography: in the morning the eastern façade throws the constellation of Orion into the building, and in the afternoon the famous three “canon lights” cut colourful beams across the nave. It feels as if time itself is invited to the service, to change the atmosphere as the day moves on.

There is a civic humility here too. Le Corbusier wanted a space that would serve a modest congregation — a place where miners and factory hands might find room to breathe. He wrote that the space must be “vast so that the heart may feel at ease, and high so that prayers may breathe in it.” That intention is visible in the way the interior manages scale: grand enough to lift the spirit, close enough to feel human.

And then there’s the acoustics — an 11-second resonance in the nave — which makes speech and song linger like a held note; it is one of those rare places where sound itself seems to be worshipped. For all its concrete severity, the church has warmth: light softening the walls, geometry offering shelter, and a gentle reminder that even the most austere architecture can be full of care.

So this Advent series ends where it began in spirit: with buildings that are not monuments to themselves but shelters for people. Firminy is a quietly theatrical finale — a place where mass and aftermath, history and hope, all sit together under one patient roof.