Sculpting the World

In Lille (France), the first comprehensive retrospective dedicated to Isamu Noguchi offers a rare opportunity to (re)discover the artist’s creations building an intangible bridge between arts and cultures, sculpture and design and also East and West.

To celebrate its fortieth birthday, the LaM Museum (Musée d’Art Moderne, d’Art Contemporain et d’Art Brut) is celebrating Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988), a major 20th-century artist, sculptor and designer at the crossroads between classical craftsmanship and radical modernity.

“For me, you know, all this story of experimental art started in Paris.”

Through more than 250 works (sculptures, drawings, design objects, performing arts pieces and photographs), the exhibition presented at the LaM is an outstanding event both as regards its scale and the variety of concerns it highlights, inviting visitors to reacquaint themselves with the kaleidoscopic body of work by the tireless artist traveller who may still be little-known in Europe but who left a lasting mark on history.

Art beyond borders

Son of the American writer Leonie Gilmour and the Japanese poet Yonejiro Noguchi, Isamu Noguchi spent his childhood in Japan. When he was 18 years old, following his comeback to the United States as a teenager, he was trained by Gutzon Borglum, creator of the Mount Rushmore sculptures. In 1927, he went to live in Paris, where he became the Romanian sculptor, Constantin Brancusi’s assistant.

“Brancusi told me once: ’You belong to this new generation who will directly go to abstraction without having to release itself from nature as mine had to do.’ I did not know how to interpret this. Was pure abstraction really a form of progress?

In this case, it is not about progress but rather something that keeps going and is imbuing the time.”

At this time, the capital was the breeding ground of young creation, and he got to know members of the avant-garde community, in particular the Surrealists, École de Paris (School of Paris) artists, and such expatriate American artists as Alexander Calder.

Although France remained an anchor point throughout his life, Noguchi never stopped travelling and drawing, nourished from all the countries he crossed and the people he met along the way, including the Chinese master calligrapher Qi Baishi, the architect R. Buckminster Fuller and the choreographer Martha Graham.

These many exchanges led him to experiment with a wide range of mediums and finally become the archetype of the total artist. He earned widespread recognition in the 1950s America, which had become the epicentre of creation, allowing him to participate in such iconic and influential exhibitions, re-enacted for some of them in the LaM’s exhibition itinerary.

Art at the heart of society

Affected by the dramas of his time and the racism he went through in Japan and the United States alike, Isamu Noguchi saw creation as an identity research for and a social activism enabling the bounds making between individuals.

In 1941, following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the artist had himself voluntarily interned at Poston in Arizona, one of the largest detention camps for Japanese-Americans. There, he hoped to improve prisoners’ detention conditions by setting to work on projects including a park and a leisure area.

Nonetheless, it was really in the 1930s, thanks to the New Deal’s program supporting the artists that Noguchi started to get into the public spatial design and landscape. He designed an earth-formed playground space that anticipated his work on the environment and garden art, such as his Jardin de la Paix (Garden of Peace), designed for UNESCO’s new head office in Paris and inaugurated in 1958.

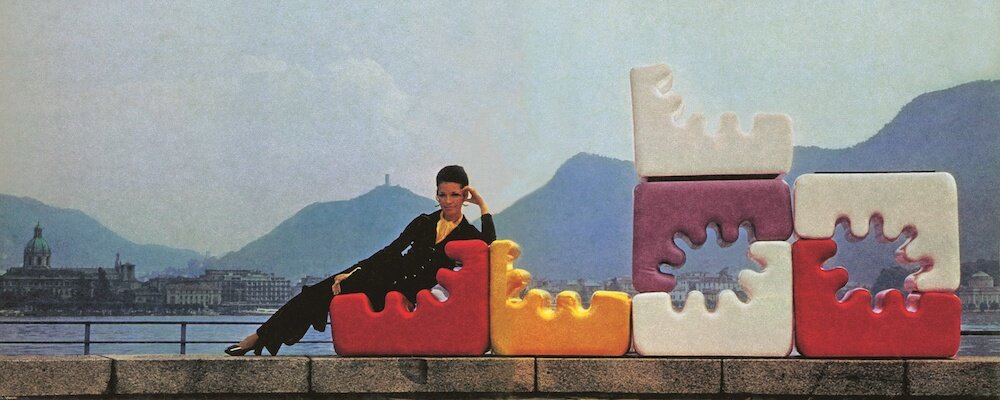

In addition to the public space, Noguchi was also interested in design and utilitarian objects. Among other things, he was the creator of the famous Akari lamps, worldwide design icons. First produced in 1952, these lamps, made of washi paper on bamboo frameworks, are the result of a combination of tra- ditional Japanese art and more contemporary forms. To extend his practice, Isamu Noguchi also designed numerous objects for everyday use, including the first electronic baby monitor, organically shaped tables or prototypes of futuristic cars as well.

Sculpting the world

Determined to “go beyond the art of objects”, Noguchi was fascinated by the relationship between sculpture, space and the body, as underlined by his various collaborations with the worlds of theatre and dance.

1926 saw him entering this world, collaborating first with Michio Ito, one of the pioneers of modern dance, for whom he created theatrical masks. He continued this work with the American choreographer Ruth Page in 1932. But his closest links with the dance world came about through his participation in the creation of sets and costumes for more than twenty productions mounted by Martha Graham, who became a close friend and with whom he worked for almost three decades. “I have never subscribed to the idea that sculptures are just sculptures and not something that is a tool. These are symbolic or gestural tools Martha was using. They were an extension of her body”, asserted the artist, who also collaborated with George Balanchine, Yuriko, Erick Hawkins and Merce Cunningham.

“I am concerned with the spaces that interlock with form.

This is sculpture.

The human being and his myth is needed within this relationship, both as participant and as viewer. ”

Noguchi played with this same body when such well-known photographers as Lee Miller or Arnold Newman got him to pose in the privacy of his studio, a space in which he became a sculpture among sculptures.

As a real meeting point between East and West, breaking down artistic borders and categories, Noguchi embodies an open, decompartmentalised vision of art that still influences contemporary creation today.

The exhibition is divided in 10 sections:

Paris Abstractions

1930: Marie Sterner Gallery

About Human Figure

1949: Egan Gallery

Living Sculptures

1959: Stable Gallery

Beyond the Art of Objects

Light Sculpture

Landscapes of the Mind

Ceramics: Between Tradition and Modernity

‘Sculpting the world’ Exhibition, from March 15th until July 2nd, 2023.